I teach two introductory computing classes at Bard: one using Python (using IPRE’s Calico and robots) and the other with Processing. Both programming environments could be better by borrowing ideas from the other. And by better, I mean a lower floor, making it easier for newcomers to programming; and a higher ceiling, making the tool useful after CS1. Rather than concentrating exclusively on one tool, I am continuing to attack the problem on both fronts.

This post is focused on making Processing better for introductory courses; Calico is next.

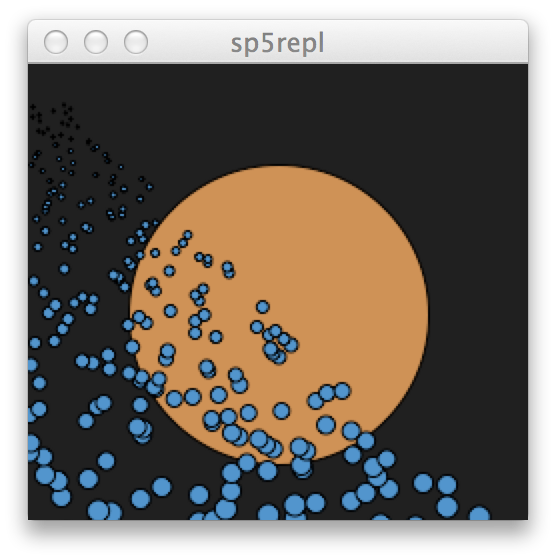

My first attempt is a simple tool called sp5repl, a small layer around Scala and Processing that allows you to write Processing sketches dynamically using an interactive read-eval-loop. The code entered into the Scala REPL is actually compiled, thus it runs at full speed; we get most of the flexibility of Jython and Clojure/Quil with the speed and error checking of Scala. A small example that generates the image below:

sp5repl>size(250, 250) sp5repl>background(24) sp5repl>smooth() sp5repl>fill(196, 128, 64) sp5repl>ellipse(width/2, height/2, 150, 150) sp5repl>fill(64, 128, 196) sp5repl>for (i <- width to 0 by -1) ellipse(random(i), i, i/20, i/20)

Continue reading sp5repl: A Read-Eval-Processing Loop with Scala